Contaminations

If in many western countries Orientalism became fashionable during the XVIII and XIX centuries, in the Ottoman Empire a similar process also happened, in the oposite direction. Through the centuries, the Ottoman architecture assimilated and added many influences to its own principles. In these two centuries, it was the winds blowing from the west that brought the Neo-classical, Baroque or Rococo styles merging them with the autochthonous architecture. One of the most eminent examples of this contamination is probably the Nuruosmaniye Religious Complex, next to Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, where the Ottoman design logic blends with extreme refinement with imported Baroque concepts.

Another example of the progressive westernization process of Ottoman buildings is the Dolmabahçe Palace, located along the Bosporus coastline in Istanbul’s European side. The decision to build it starts with the idea that the old Topkapı Palace, located in the historical peninsula, was obsolete and unfit for a modern empire – and even most when compared with its western counterparts. Suffering from innumerous changes and adaptations since it started to be built in 1455, the medieval Topkapı Palace lacked the functional effectiveness and grandeur that a XIX century palace required.

By building this new palace, the Sultan Abdülmecid I was decided to portray the empire as modern and still powerful. The reality was different, though. By then, the country was known as the ‘’Sick man of Europe’’ and the money spent building it – a quarter of the country’s GDP and an approximate equivalent of 1.5 billion USD today – only helped the economically debilitated state to go bankrupt a few years later. The work was commissioned to the court architect Gabaret Balyan and one of his sons who studied architecture in Paris, Nigoğayos Balyan. Most of their work was strongly influenced by French architecture and this is very patent throughout most of the palace.

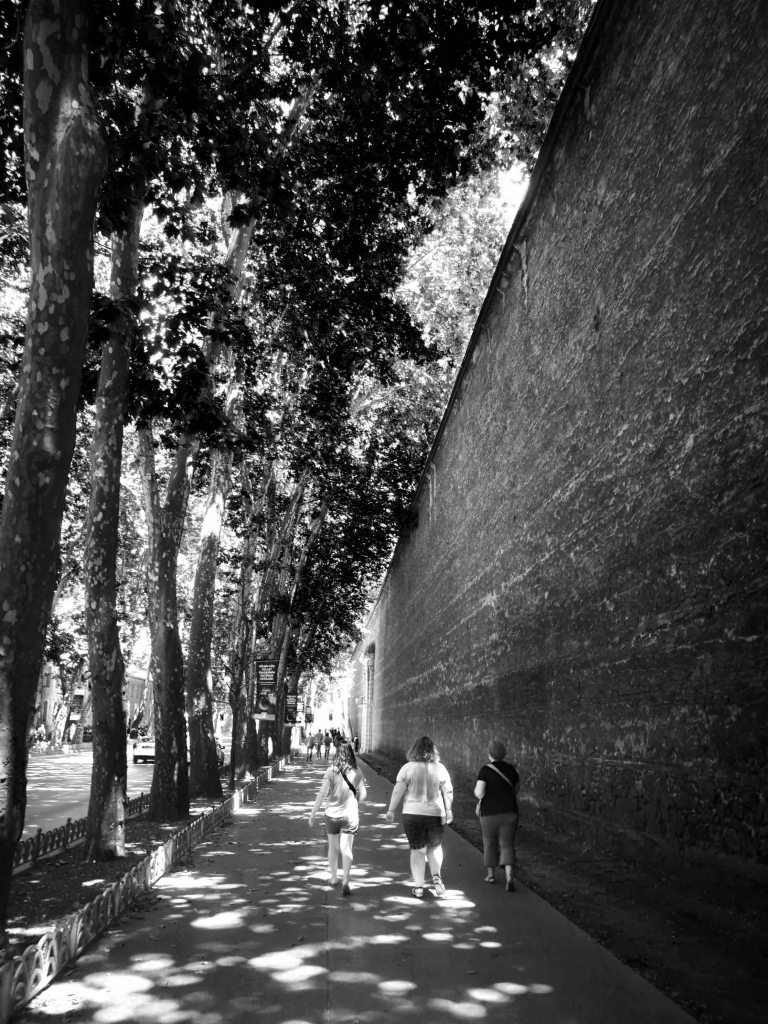

For an architect, one of the most striking features of the whole project is the fact that the buildings are designed towards the Bosporus and not facing the city. Its display of Rococo detailing and complicated overdesigned elements are shown to the ones arriving from the sea or passing by boat. On the opposite side, the façades facing the Dolmabahçe Avenue, are mostly hidden by high walls and can only be partially seen from the outside through the few monumental gates placed along them. Only the visitor or the Bosporus traveler can get a full vision of the large elongated construction.

From the southwest side, the visitor is offered a sequence of architectural moments that start by a lighthouse like watch tower that marks the entrance before you pass the gates. After crossing this jewelry work carved in marble, one views the main lateral façade of the Selamlık – public part of the palace – across a simple French garden, which reason to exist is to reinforce the strength of the Neo-Classical entrance. The gardens are populated with local and foreign species in the best botanic tradition of the epoch and it also has its English romantic garden corners, mostly close to the bird cages, where a small lake displays a beautiful coral shaped sculpture.

When in this area of the palace, one might feel displaced and with the idea of having been transported to some village in central Europe. The small supporting pavilions are clearly inspired in European townhouses, using wooden structured roofs and brick and mortar façades.

Although its plan and setting is quite rational, the building keeps most of the elements of the traditional Ottoman palace life, visible both in the public as in the private areas.

The most imposing space of the palace is the Ceremonial Hall (Muayede) which functionally articulates the two main sections of the building, the public and institutional with the private and residential. This hall is one of the paradigmatic spaces where the syncretism of eastern and western styles becomes more clear and beautiful. If its axiality and hierarchic importance comes from the French palace tradition, the solemnity and spatial reference comes from the Ottoman praying rooms.

Nevertheless, the decorative formalisms of Neo-Classical and Baroque character are imposing throughout the whole complex and it is the local aspects that become almost residual, delegated to mere secondary role. It all reveals the wish for change and renovation. The amazing Bohemian and Baccarat crystal chandeliers, the fresco painted ceilings and walls with tromp l’oeil architectonical effects, the Japanese room or the European collection of paintings are all marks of a change process in taste.

The public-private separation was common to most palaces built at the time, the difference of Dolmabahçe from the western typologies was that the female presence was not allowed in the public activities happening at the Selamlık, being only allowed to watch the grand ceremonies through grilles. The Harem – private quarter – comprising a larger area than the one for official formalities, accommodates the bedrooms and the complementary rooms for the Sultan, his mother and eight apartments for his wives and concubines. In this matter, Dolmabahçe remains very Ottoman…

Dolmabahçe was the largest, most sumptuous palace ever built by the Ottomans. It would take more than 100 years so that another palace would be built in the country but, if Dolmabahçe was a vision with a modern westernized flavour, the new presidential palace looks back to the past. The reasons and ambitions for building them were similar, but the latter lacks the sophistication and knowledgeable taste of the former.

2 thoughts on “Occidentalisms in Ottoman Architecture”